Gowander1

Wander gets out there

For near, far,

and lucky escapes

Gowander1

Wander gets out there

For near, far,

and lucky escapes

Enough talking, a trip is in order!

We'll be escaping London to explore England and beyond.

And you can always find out where we've been

and what we've been looking at on our tumblr

From the Maginot Line to the Maunsell Forts

From the Maginot Line

to the Maunsell Forts

Of A Bunker Disposition

From the Maginot Line to the Maunsell Forts

From the Maginot Line

to the Maunsell Forts

Of A Bunker Disposition

This is a journey through seascapes and snowscapes, through bizarre and banal. A story of frontiers and fluid borders. But most of all, of a slow burn obsession shared among friends that took them from Alpine to Estuarine: bunker research.

Modernism in the Mountains

Modernism in the Mountains

Modernism in the Mountains

Modernism in the Mountains

Max and Camille are free-spirited Englishmen with a continental connection. Max breeds envy among friends as they follow his frequent posts from atop an Alpine Col. Camille is holed up high in the Pyrenees but originates from the flatlands: “I grew up in East Anglia," he reminds us, “Iʼm from a bunker disposition." As cyclists, their way with two wheels gives them the ability to rise and explore, criss-crossing mountain paths to shift perspectives and unearth the unseen. As writer and photographer respectively, they trace ridgelines with complementary tools and distinct attitudes.

Cycling whets the appetite for exploration, pushing that bit further and higher to find the places others —literally— cannot reach. For Max, his Alpine journeys began to reveal strange forms, which through a little research, shaped into something more concrete: Bunker Research, a book that documents the hidden history of modernism in the mountains. Among the Alpine Extension of the Maginot Line, a handful of isolated fortresses lie marooned among remote and endless landscapes. “I became obsessed by the bunkers,” says Max, and thinking that Camille might share his fascination, “I dragged him over to the Alps” he adds, “which was not his natural habitat.” And so the pair went bunker-hunting.

Their bunker research wends its way up the mountains, from the pleasure-palaces of the Cote DʼAzur to the barren peaks of the Cime de la Bonette. The contrast of rugged swathes of nature punctured by clean concrete fortifications is striking, and begs the question: How did they get here? Who built these? Ironically, many of the forts on the French side were built by Italian contractors: supposed enemies during wartime, yet trading partners for Millenia.

© Camille Macmilan

Maunsell Fort Madness

Maunsell Fort Madness

Maunsell Fort Madness

Maunsell Fort Madness

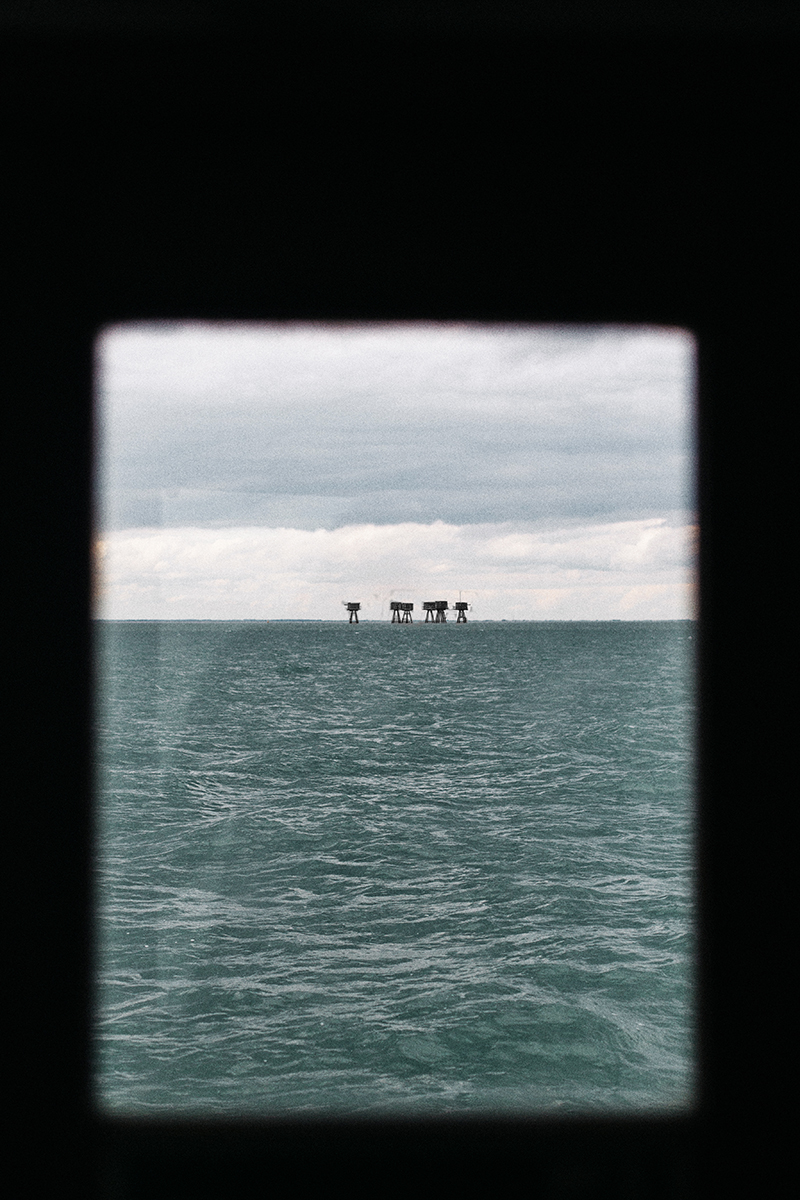

Rarely content to settle, the bunker obsession led Max and Camille on a different journey in search of imposing architecture and spirit-level Estuaries. We turned a grey North Sea sailing into a hunt for mythical Maunsell Forts, gathering a motley crew of writers, artists, curators and photographers along for the ride. Brutal yet beautiful, these alien structures were built during WW2 to protect London and the British coastline. Prefabricated and anchored miles off Kent, they formed a cluster of fortresses that became the first defence against enemy fire. “I do find them threatening,” says Max, “Britain is an island. Yet France and Italy have been at war for a thousand years. We always have these clashes in the most unlikely places. The places in-between are in the end where we come into conflict.”

Our trip to the Forts comes at a heavy moment. Camille never makes it. “Tell me the UK is not as bad as I am reading from here,” he writes from the peaks in the Pyrenees, “From this mountain I canʼt tell anything!” Barely days after Brexit there's a looming sensation that the country is turning backward and inward. So it's poignant that we're headed out to experience these echoes of architecture, fortresses built to protect freedoms and borders during testing times. “Maybe we could start a kind of reverse Dunkirk evacuation?” mails Camille as the trip approaches. And as we board the trip feels like both escape and defence-mechanism: a fingers-up at countrymen who now feel like the enemy.

Borders and Bunkers

The Forts grew out of an era of division and protection. A special-interest library on board reveals strange Wartime stories. Servicemen were known to suffer Maunsell Madness, spending weeks stranded in the disorienting tides of the North Sea. “The chief enemy, apart from the Germans, was monotony," or so the book states. To resume some semblance of normality, a fortnightly exhibition of craft was encouraged, and military personnel became experts in knitting, embroidery and toy making. Set this against their strike rate — 21 enemy bombers shot down — and you reveal the haunting contrasts of everyday life in times of conflict.

But it's never as simple as 'us' and 'them'. “I think the channel has always been a psychological border and that makes the Maunsell forts different," says Max. "Theyʼre stuck in a no-mans-land between the UK and the continent. But the bunkers we went to look at were are so provisional as that border has shifted so much, that I donʼt think it's something we can understand.”

Photographs © James Devereaux-Ward

Pirate-Style

Pirate-Style

Pirate-Style

Pirate-Style

Buoyancy and Bravery

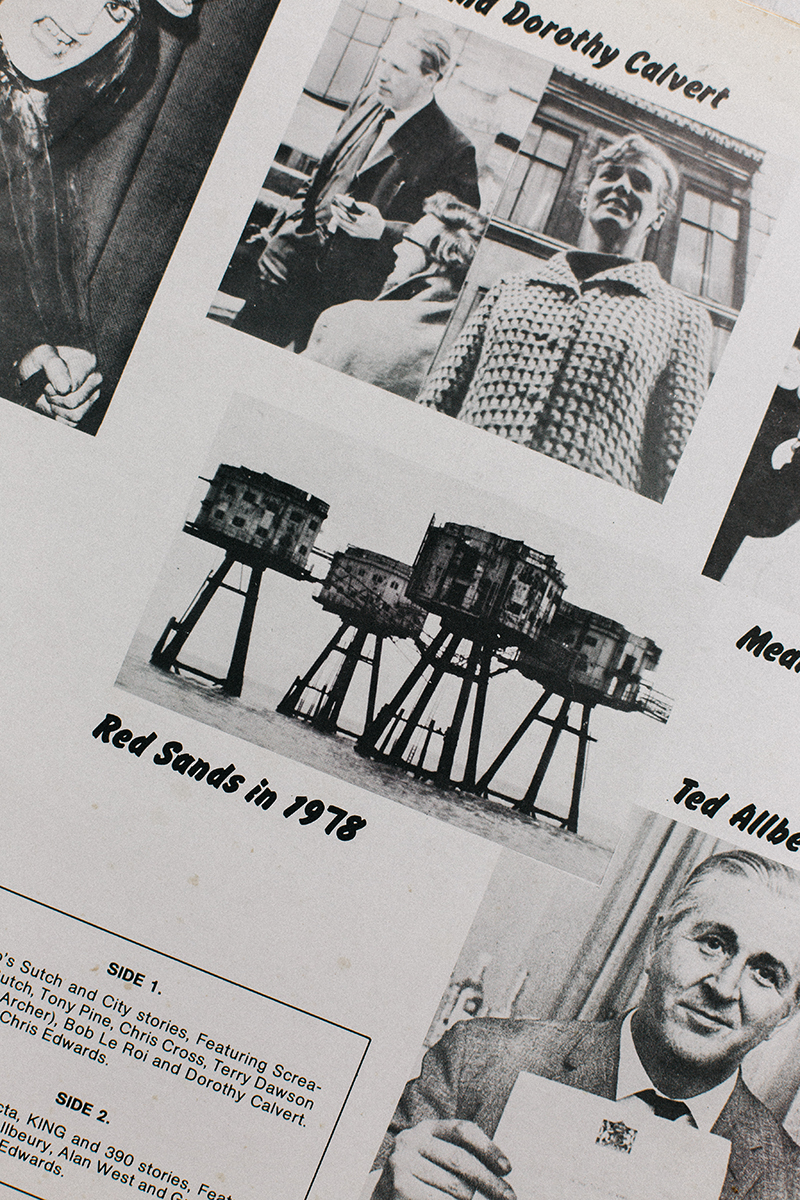

Enough about War, let's turn the mood buoyant. The on-board historian, David, is no specialist in combat but rather an expert in the second-life of these structures, and suitably anti-establishment. All hail Pirate Radio. Digging out a vinyl record of interviews —“Itʼs rare as a rocking horse, this” — he sets the scene. In their post-war revival, the forts started out as smuggler's haunts. Tom Pepper, a local fisherman with a love of contraband, dreamt up the idea to make use of the forts for their limbo status in international waters, and offshore radio began. During the 60ʼs, the musicians unions enforced ʻneedle timeʼ which meant there was little to no popular music on UK radio. Sitting 3 miles beyond the limit of territorial waters, the forts were re-imagined as home to new music stations, pirate-style.

They weren't all glitz and the elements and the authorities were now the enemy. Tom came to a tragic end, heading ashore for Christmas with a DJ and engineer, when their boat took on water and sank with no survivors. Tom's body was found near Whitstable, and an unidentified body washed ashore on a Spanish beach with Radio Invicta tapes still in the pockets. The radio was reborn and became 390 (inspired by the wavelength). Despite its illegal status it attracted up to 2.5 million listeners a day. But the Admirality cottoned on and played dirty: dredging sand to create a sandbank close to the Forts they planted a flag and declared the seabed Crown property. Defeated by legal loopholes, the station shut down, and the forts stood as rusting reminders.

Rust and Resilience

Now the custodians of the structures, Project Redsands, patch them together with volunteers, and chug out boatloads of Russian games designers, German slack-liners and the US Ambassadors. It's not cheap to keep the rusting hulks and time and money is running out. “There's plenty people curious, but we need help,” pleads Captain Alan, “Weʼre all getting old.” There are parallels with the state of the Maginot bunkers. But why not let them decay to oblivion? “The Maunsell Forts and the Bunkers even though theyʼre in different places are reminders of things weʼd rather forget.” says Max. “Theyʼre feelings of enmity, and hate, and opposition.” In an uncertain Europe of nervous neighbours and contested borders theyʼve acquired new relevance as monuments to a time before our union. “And I think theyʼll be here forever,” says Max, “I think theyʼll be here longer than us.”

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

The BOOK Bunker Research

Rise from Côte to Col as you track Max Leonard and Camille Macmillan's journey

into the hidden history of modernism in the mountains.

THE BOAT X-Pilot

The only vessel that will always make it out to the Forts.

Call Martin Harmer to check sailing times and book your space on the boat

Project Redsands, the volunteer group that act as guardians for the Forts

might allow you to board it in return for time or skills (from welders to fundraisers, they're looking for help)

THE BEST Pirate Radio Hall of Fame

Honour the stars and broadcasters from the golden era of Offshore Radio

As ever, Vice got there first, and brought old and new pirate radio DJ's together to meet on-board

Big thanks to James Devereaux-Ward, Max Leonard and Camille Macmillan for their creativity,

Jes, Jess, Nancy, Eloise, Luke, Sam, James, Liam for being pirates for a day,

and the whole X-Pilot crew for the ride!

To Southend-On-Sea

To Southend-On-Sea

In Search of The Wild East

To Southend-On-Sea

To Southend-On-Sea

In Search of The Wild East

“Ken’s a legend,”writes Thierry to me earlier that day. He’s not wrong. Ken Worpole's book The New English Landscape opened my eyes when I first read it, turning my under-appreciation of Essex into something close to unconditional pride.

I’ve been shuttling out to the Essex coast for nearly 20 years, to the extent that I can recite the Fenchurch St to Shoeburyness line in my sleep — Basildon, Pitsea, Benfleet — But I grew up among rolling Hardy hills and clear Purbeck seas. At first I felt let down by the brown wash of estuary and pylon-laced fields: the edgeland landscape that emerged east of London. I'd venture out longing for an escape and return home with a head full of grey in winter, stinking of chips and sunburn in summer. Turns out I just wasn’t looking right.

Focal Point

focal point

Ken Worpole, The New Life in Essex

7pm, 12th May, Focal Point Gallery

Focal Point

focal point

Ken Worpole, The New Life in Essex

7pm, 12th May, Focal Point Gallery

“If you know the history, the whole landscape comes into focus,” says Ken.

Revealing a place’s hidden past alters your understanding of the present. With that mindshift comes an awareness of alternative possibilities: of a future emerging from a place, and of different experiences to be had within it. It’s not about a ‘New’ landscape, but rather a ‘New’ point of view.

That’s the ambition of the Radical Essex project. Can we imagine Essex in a different light? A kind of 'Wild East' of pioneers and revolutionaries. It has its fair share of fake tan and boy racers — an Essex girl would be the first to admit that — but what of the soaring estuary skies and slivery flatlands, the rich wildlife, the ancient fortresses. Think of those loveable Essex boy qualities of endurance and resilience; the deep respect for family and community; that independent, entrepreneurial spirit.

I’ve always warmed to people from Essex. Not too uptight, always up for a laugh, “a bit rough and ready” says Ken. These abiding mentalities mean that it was a place always open to people living within the landscape in alternative ways. Whatever goes, goes.

And it went: From Britain’s first naturist colony in Wickford to self-build communities inspired by anarchist architect, Colin Ward. Just part of the little-known history of radical politics, lifestyle and architecture that the project aims to uncover. More recently it’s welcomed “A House for Essex” created by TV’s favourite cross-dressing potter. Not only was Essex a place for different modes of living, it was an escape from the confines and hardships of 20th Century East London, a therapeutic haven available for all. “Driving out to Othona is like driving to the edge of the earth” says Ken, talking of this sanctuary settlement way out on the Dengie peninsula. Canvey Island once claimed to be the ‘Healthiest Town in Britain’. Meanwhile, Hackney decamped en-masse to the caravan parks of Wrabness to take in the fresh air and watch the tankers promenade past.

Downriver

And yet Essex was a landscape deemed to to be of little value — in the traditional picturesque sense — which made the perfect testbed for reinvention and experiment. “We’ve been throwing things away for centuries, only realising that there is no such place as away. We all live downriver now,” concludes Ken in the New English Landscape. This is a place shaped by man-made ambition — take Thurrock’s massive Superport — but also violent force of nature, like the devastating Canvey Island floods in ’53. “Where’s the thinking that integrates our houses into the landscape?” concludes Ken, “We have to re-learn to make habitats for people to live within the landscape, and Essex has a head start on everyone else.”

Flood House

flood house

Southend Pier, 12 May, 8.30pm

Flood House

flood house

Southend Pier, 12 May, 8.30pm

“Unlike landscape, the sea has no past, no topography, Man’s presence on it leaves no mark; it is never still. Look out on it, try and define it and like Conrad, you will reveal only your innermost thinking. You can no more describe the surface of the sea that you can the surface of a mirror.” Phillip Marsden

In a place where sea, sky and land meld, the coastline dominates Essex. Here, people have long lived with the shift of tides and mudflats literally changing the ground beneath them, learning to adapt their ways of living to suit. That nimbleness is the ‘head start’ that Ken alludes to, and The Flood House, in the spirit of Essex living, is such an experiment. It floats an idea out there, and asks to imagine what it could be like to live among the seasonally-flooded seascapes. Designed by Matthew Butcher, the structure will drift from mudflat to mudflat throughout May, monitoring the weather conditions of the Thames Estuary.

“Where’s the Flood House tonight?” I ask at the Focal Point Gallery, as they kindly look up tide times.

“Oh, it’s out there, tonight’s it’s last night in Southend” beams Jes Fearnie, the House’s curator.

“You’ll find it moored opposite Adventure lsland. You’ll see the cargo ships in the distance. They’re beautiful!”

I’ve always had a soft-spot for industrial shipping, so I head to the seafront to find lights pulsing along the longest pleasure pier in the world. Last time I walked it was a reconnaissance trip for a friend shooting Alison Moyet’s comeback video. What better emblem of Essex for a Basildon girl?

Adventure Island

Sea and sky have taken on blue and lilac hues, and the Flood House pops yellow gold against the dusk. Pointing my camera out across the water I come across a pair of well-groomed charmers who work the late shift at Adventure Island.

“What is it?” they asked, genuinely curious. “Is it a toilet?”

The form is based on bunker architecture, and seen from the shore it does have a utilitarian, somewhat sanitary air. So not an unreasonable question.

“It's a prototype for living on the sea” I smile, and hand them a Flood House leaflet from my bag. “If you go to the Focal Point Gallery, they’ve got the key, you can have a look around.”

“Ooh, you’re like Mary Poppins, you’ve get everything in there!” waving as they walk off. Aren't people just more fun in Essex?

Balmy

I bet it’s balmy out on the Flood House this evening. The sun cascades purples and pinks to silhouette the gardens behind; couples stroll and cars rev down the seafront. In the distance, the lights out at Sheerness Car Port flare and sparkle, as the structure bobs tiny among this vast seascape. I don’t want to go back to Hackney. I miss the sea. “Let’s buy a big plot of land and all move here” jokes Joe Hill, the gallery’s director, cajoling us all into a new life as the talk ends. Where’s the future in London? The only way is Essex.

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

The Knowledge

This essay recounts an evening in Southend to hear Ken Warpole's talk at the Focal Point Gallery 'The New Life in Essex: Nonconformist Life and Culture in the 20th Century'. Thanks to those below for organising the event and the new take on Essex it's offered us:

Ken Worpole

Ken Worpole is the author of many books on architecture, landscape and public policy, and two notable works on Essex, the county in which he grew up and has been exploring ever since: The New English Landscape a chemistry of word and image created with photographer Jason Orton documents the changing landscape and coastline of Essex and East Anglia, particularly its estuaries, islands and urban edgelands. 350 Miles: An Essex Journey precedes it.

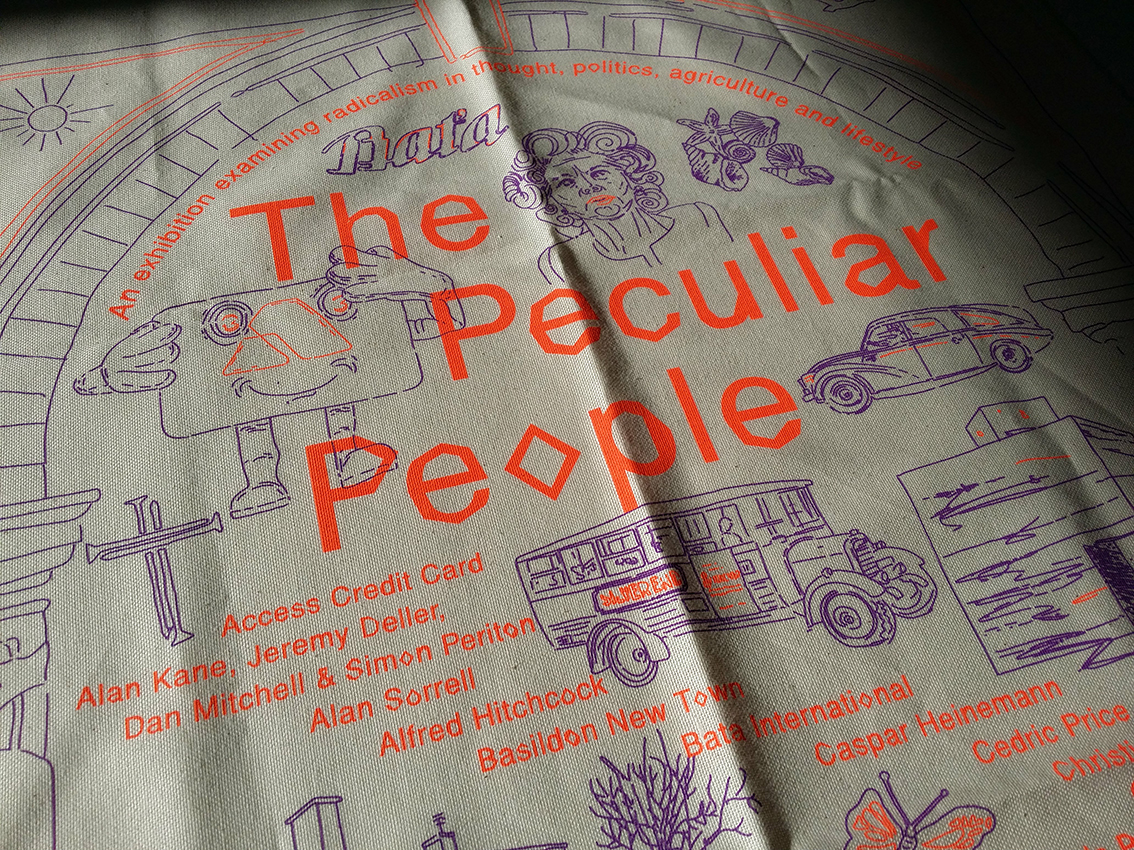

Radical Essex

Radical Essex aims to re-examine the history of the county in relation to radicalism in thought, lifestyle, politics and architecture. A programme of events will take place across Essex throughout 2016 and 2017, shedding light on the vibrant, pioneering thinking of the late 19th and 20th Centuries. It’s an interesting partnership between Visit England and the Arts Council, using cultural tourism to shift perceptions of place.

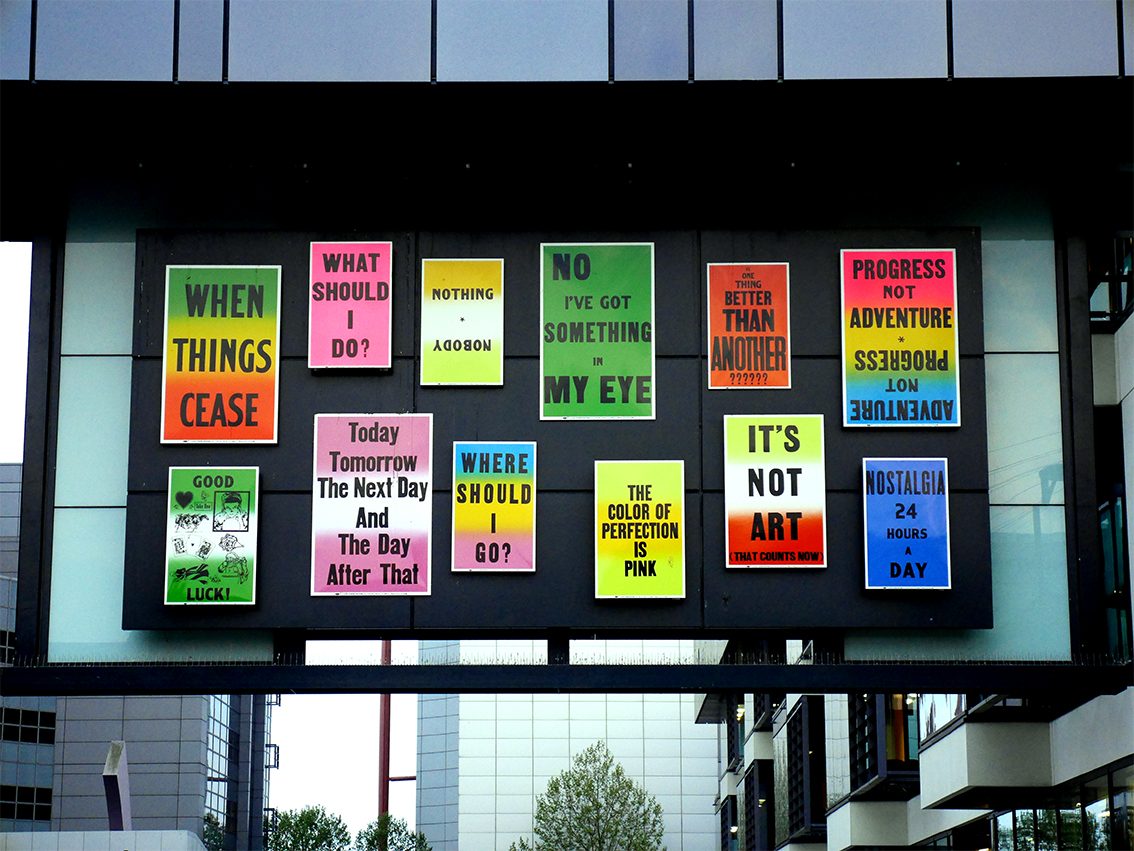

Focal Point Gallery

Flying the flag for Radical Essex is Focal Point Gallery in Southend-on-Sea, a brand-spanking new centre for contemporary visual art and events, as well as offsite projects and public artworks. The launch exhibition for Radical Essex, Peculiar People feels like a weird and wonderful archive of anarchism, and a springboard to exploring an alternative side of the county. The good people of this gallery know how to show their guests a good time and guaranteed you’ll have a truly Essex welcome — thank you for the tea towel souvenir Joe Hill!

Flood House

The Flood House will be moored at various sites in the Thames Estuary in April and May 2016 and will drift from mudflat to mudflat as if in a future flooded landscape. You can track it’s current location and check live weather readings out on the Essex coast.

Into Essex

Head East. The C2C line will take you out to the coast along marshes, container ports and ancient villages-turned-commuter towns: Rainham Marshes, Tilbury Docks, Canvey Island...But the overiding theme of Essex is that anything goes, so you'll find everything from the Art Deco and Streamline Moderne village of Silverend to highly conspicious secret nuclear bunker at Klevedon Hatch

Photography © Rosanna Vitiello

Map, courtesy of Essex Records Office, from the New English Landscape

To Oporto

To Oporto

for a dinner deconstructed

To Oporto

To Oporto

for a dinner deconstructed

Tell me what you eat and I’ll tell you who you are

Brillat-Savarin

We ate Porto up. Devouring every corner of the city, savouring every story we encountered. Four days into our discoveries, the summer school gathered around a celebration of food. Based on the notion that cooking and eating can be one of the most profound and intimate experiences you can have with a place, we tucked into Porto.

The vocabulary of eating and exploring and intertwined: when we’re curious, we say we’re hungry to know more; if we’re keen, we say we have an appetite for knowledge. Interesting ideas emerge from mixing the two worlds and to discover this city we borrowed from both: Can you taste a landscape? Can you savour the identity of a place?

“People love to eat context,”said Bruno, who together with Ana, helped us to create a feast. He turned mere grocery shopping into a grand tour of the city’s food shops, markets and its character. As we crossed each ingredient off our list, a new tale was exchanged. What follows are notes captured from these conversations: a dinner deconstructed to digest the identity of Oporto.

To Oporto: Part 2

The Ingredients

To Oporto: Part 2

The Ingredients

Tripe / Tripas

An unusual place to start thinking about dinner, but we have Lin Yee to thank for that. Her tripe-obsessed project takes a new angle on innards, and Tripeiros, as people from Porto are called. Shopping for cows stomach isn’t everyone’s idea of a great time, but she’s in good company. On childhood vacations my relatives would show off the neighbourhood display of intestines as a matter of pride. It became an initiation rite into local culture, and so this tripe tour of Porto takes on an air of nostalgia. Our third partner in crime is Bruno, a renowned carnivore who knows the ins-and-outs of every butchers' shop in town and whose love of tripe is not for the squeamish.

To eat is to exchange, and as we tour we trade blood tales from China, Naples and Northern Portugal; pork blood cubed and jellied; blood-enriched chocolate sauce and stew. Bruno trumps us with an account of pig slaughter: holding the cord around the pig's neck while his grandfather finished the job. “The blood went everywhere. I looked like a ten year old who’d brutalised a whole village.”

I know what you're thinking. What a holiday? If you're in London, the closest you'll get to such a tour is The Tripe Marketing Board's genius that is Tripe-Adviser. But in Porto – of all places – tripe is taken seriously and every part of the animal is used. On the spotless counter at Carnes Silmor we count lungs, lips, pigs tails, blood cakes. True to Porto's past, tough times demand we're inventive with cheap cuts. Lin Yee takes it to another level and sees appeal in its coral-like texture. She spends hours the next day scanning honeycomb tripe for the travelogue, and in black and white it takes on the feel of folds of a wedding dress. Meanwhile, intestines go down well with our unsuspecting guests: parchment white, cut into two inch lengths, battered until crisp and served with lemon and salt. And so the meal begins.

Greens / Verduras

A matriarch with wraparound shades commands the corner plot at Bulhão Market. “I like to spread the love,” jokes Bruno, as we walk from stall to stall surveying swathes of veg, and buying a little of what we fancy from each. White-haired ladies line the crumbling aisles, and address him as "meu filho" my son, "meu amor". There's nothing like a spot of market shopping to boost your confidence.

We gather onions and ask our matriarch for a photo that costs us a cool 25 cents. But peddling vegetables doesn't pay the bills, and you can't blame these ladies for trying to make a little extra. A couple of stalls down, our permed stall-holder jerks her finger towards an unplugged chest freezer. We pull out fat-bottomed aubergines to char on the barbecue and smash down with tart garlic and grassy olive oil. We side-step towards weighty beefsteak tomatoes, gnarly and ugly and big as our heads. They smell of deep green in the way only a hot-country tomato can. Sliced up that evening the flesh is marbled with reds and pinks. “You don't want blueberries?” hawks the vendor wife. “Maybe a pack of chillis?” She's got the hard sell which is why she's got the biggest stall. It's a husband and wife operation, and I spot a secret pin-up hiding on the back of a hand-cut price tag that nestles among the tomatoes. I imagine this must be his hidden respite from his pushy mulher.

Back in the kitchen, Ana’s thing is greens and she makes magic with them. Two good handfuls of ruler long beans are tossed and fried tempura style, served with paper-thin lemon slices. Crisp green, sweet and floral. Courgettes are cut into chewing-gum-thin slices, rubbed with salt, sugar, lots of garlic and savoury rosemary. Left to wallow for a couple of hours then rinsed, they transform into a semi-cured ceviche of zucchini. Sweet potatoes soak up a smokiness as they're slow roasted over coals. Cut into melting chunks, they meld into a salad, their softness contrasting with the bite of apple and garlic slivers. “This was so good it made me cry,” say the Kuwaiti girls and Ana beams proud.

None of this is traditional, but no-one seems to have cared too much for vegetables in Portugal. The earth, a terra, was always the last resort for food. Some people say greens represent a hand-to-mouth peasants' past that people are keen to forget. Meat is equal to wealth, but these are not wealthy times and there's less need for a heavy meal to set you up for a day's hard manual labour. Tastes are evolving as influences from outside infiltrate: “I am a purist,” says Ana. “Thats what I like about Nordic cuisine. You know, BAM! Just a turnip,” and cracks a wry smile.

Meat and Offal / Carne e Miudezas

The butchers shops have a particular look: a post-modern 80’s vibe brought about by chilled grey granite and pink fluoro lighting. At Carnes Silmor, we step into immaculate meat lockers, like closets kept for best. Out back, butchers heave heavy half-moon knives as they expertly cleaver each carcass. Hosepipe lengths of paprika smoked linguiça sausage are slung around hooks on the back wall. Layers of secretos line well-kept glass counters: a Portuguese secret as the most tender part of the black Iberian pig.

We stop into another Talho to see what’s good, and pick up a plump veal heart. The manicured butcher carefully wraps the organ, and hands it back in a dove grey bag borrowed from an Italian children’s boutique, printed with the words 'sogno di bambino'. “You have to pay for bags now,” says Bruno as if to explain the bizarre combination of a heart packed into a little boy’s dream.

In the kitchen, we’re shown how to dissect it and it forms the base of a flavoursome stew braised until melting on the barbecue. Sweet with onions, made earthy with livers, then seasoned with bay and just enough chilli to make you blink. Portugal can handle a little spice, a taste that connects to colonial times and a piri-piri punch that's been brought back. A few nights earlier Filó, Porto's beloved Angolan chef, hands me a grin along with an industrial sized jar of piri-piri for which she is known. "In Africa, we make our moamba really spicy," she says, "But I let everyone here choose for themselves."

Bruno gives us a gift of oxtail. A shank lies out on the side which Lin Yee learns to cut under his guidance. It’s braised until almost sticky with tomatoes and deep red wine, while we’re entertained with teenage stories of riding bulls drunk (it only happened once). At the end of the night, Casey lifts the lid off a vat of Arroz de pato: soupy duck rice, laden with duck meat, blood sausage, linguiça and bay. Some guests are on the verge of an Irish goodbye, only to have the waft of meat and rice reel them back in, plates in hand.

Salt Cod / Bacalhau

The tang of salt cod gives a sharp slap up the nose as we turn the supermarket aisle. One-metre slabs of bacalhau lay loose in a corner, mummified like ancient artefacts collected from faraway seas. Organised by different grades from miudo (a little one up to 0.5kg) to graudo (a grown cod up to 3 kg) the oceans of origin are also noted. The dark waters of Iceland or Norway seem at odds with the shrill heat of an August Porto day.

Deema asks a reasonable question, “Why do you go so far for fish when you have so much right here in the Atlantic?” Bruno introduces me to Fernando Pessoa’s ode to Portugal A Mensagem, The Message, and it offers a roundabout answer. Entitled ‘O Mar Portugues’, The Portuguese Sea, the whole of the second chapter represents past glories. The sea is hailed by Pessoa as a memory of the Portuguese talent for exploration: a small nation which turned its back on Europe, set its sights afar and navigated the globe. And bacalhau, a by-product of those ancient mariners, is a taste of that past once nicknamed fiel amigo or loyal friend.

Each season, the famed White Fleet crossed the Atlantic to set sail for the cod-rich waters of Newfoundland. Woven into the folklore of Terra Nova are the dory boat men who each day handlined cod, then split, gutted, and salted for sale months later on the mainland. Now, mothers of Portuguese friends abroad still send packs of salt cod with love, a memory of home and icon of identity for their emigrant offspring.

Days of soaking soften the rock hard flesh as Portugal’s past awakens and takes on a whole new texture. The ritual of desalting a bacalhau takes time, more than we have this evening, so we come up with an alternative. Our salt cod is whipped into an addictive bacalhau a bras: shredded, worked through with stick thin potato chips, softened onions, bound with beaten eggs and flecked fresh parsley. I enjoy it so much I eat it for breakfast the next morning.

We buy a dried miudo slab just to show our guests. Ana pierces it with a good thwack and it's hung on the door:

the first part of an impromptu sculpture of sea, land and people. With a bit of digging, I find the fabled poem which is suitably dramatic:

"Salted sea, how much of your salt comes from tears of Portugal!

Mar Português

O mar salgado, quanto do teu sal

Sao lagrimas de Portugal!

Por te cruzarmos, quantas mães choraram

Quantos filhos em vão rezaram!

Quantas noivas ficaram por casar

Para que fosses nosso, o mar!

Valeu a pena? Tudo vale a pena

Se a alma não e pequena

Quem quer passar além do Bojador

Tem que passar além da dor

Deus ao mar o perigo e o abismo deu,

Mas nele é que espelhou o céu.

A Mensagem

Fernando Pessoa

Octopus / Polvo

Sara the fish wife, seems nervous. The three plump octopuses we had our eye on a minute ago have now swiftly disappeared. “You know what’s happened?” says Bruno “There’s an inspector circling the market.” Sara tries to look busy, frantically scaling a sea bream, as we arrange to rendezvous for the polvo in twenty safe minutes.

Meanwhile, we swap stories to pass the time: of a Galician friend who could read an octopuses mind, stalking rock pools to return with a glut of 20; Of immense pulpada octopus parties, where cooks dressed in white lab coats to protect from smears of black ink; Of one grandfather returning with 6 huge olive oil cans full live squirming creatures, ready for the deep freeze. There's something lavish about an octopus that makes for generous anecdotes.

That evening, our eight legged friend is made into a fresh salad: braised and chopped purple with garlic, onions, parsley and pepper. This classic makes an unlikely madrugada comeback, as we leave a club a couple of nights later and Sergio tells me he’s off to eat an octopus salad sandwich.

Fruit / Fruta

Sol, sol, sol! The sweet Mediterranean climate brings abundant fruit harvests. I always think of Portugal as Atlantic, but Ana reminds me that it dips a southern toe in Mediterranean waters. We pick from its bounty; Seven-year melons encase striking white flesh and black seeds; Green and dusty purple figs, still small as it’s early in the season; Jen and Jess bring a peach they find growing wild at the granite works; Wine-sweet grapes from the Algarve are bought to accompany strong São Jorge cheese; A fragrant pineapple gets forgotten, but we discover two types exist in the Portuguese-speaking world : ananas, and abacaxi, a sweeter variety that Brazilians blitz with hortelá mint.

People / Gente

Ok, they're not on the list but good people are always the main ingredient. Kate's hand-drawn Rooster of Barcelos is slowly surrounded by snippets of conversation. Ideas exchanged from Finland, Kuwait, Italy, Russia, Lebanon, India, Israel America and Berlin make for a heady mix. Behind the symbol that adorns every tourist tablecloth in town is a story of a foreign traveller to Portugal who was saved by a culinary miracle (and, no, that's not Nandos). Bruno has a theory that it was the cook's ingenuity, rather than divine intervention, that caused the roasted cockerel

to crow, and the alternative history seems appropriate tonight.

Dessert / Sobremesa

No one makes it to dessert. Bags of sugar are left unsealed, eggs unbroken, lemons unskinned. Guests normally bring a sweet, so Ronit tells me the story of her mother Malka’s cheesecake. She passed away some years ago and it's traditional in Israel to commemorate the date. Food is so tied up with memory that the family makes a meal. She wasn't renowned as a great cook, and her Friday night offerings were often one colour: everything white or everything red. As part of her white meals she often made a wonderful crumb cheesecake, so good, it’s now made it onto the menu at Ronit’s husband’s restaurant.

Mika ends the meal with an evocative turn of phrase. “These sundown sessions were like dessert,” he says. A sweet surprise at the end of each day, a pause that turned the conversation over.

To Oporto: Part 3

The After Party

To Oporto: Part 3

The After Party

Time to digest. The week’s exchanges flow back into mind as the table is cleared and laid afresh. Porto is a city in search of new narratives. As we cracked open its character we found a handful of ingredients: Alter-egos, shadows, granite, peaches, tripe combined to make who knows what?

Tastes are slow to change, but our chef-accomplices are inventive enough to shift them. “Portuguese food is characterised by inertia”, says Bruno, “but we’re trying to lighten it and present it in a new way.” They’re masters of reinvention: a law student (Bruno), an urban planner (Pedro Limão) and a sculptor (Ana) who all turned to cooking as a creative exploit. Together they explore projects that break our traditional conceptions of food, and embrace that once famed Portuguese talent for exploration.

I sit down with Ana. Cigarette on lips, with striking cheekbones and quick-witted almond eyes, she looks like a strong female Corto Maltese: “I’ve worked in restaurants for a very long time. Good ones. And I’ve become tired of the dynamic. Ok you create a menu, that’s interesting, but after that it becomes very routine. I want to create something that changes that. To cook for people in a different context, a site-specific work that shows them where food is from. Its the best way to understand a culture.”

If Portuguese identity is back on the drawing board, food could be part of that blueprint. But it’s not an easy time to be in Portugal, and it takes a certain attitude to conquer the ever-present air of adversity. Over a bittersweet coffee, Bruno reflects: “It’s not confidence, it’s something that catches you before you hit rock-bottom.” He talks of how this city leaves a taste of past greatness that fills you as you walk its streets, and I leave hopeful, that even in its decline, our appetite is whet for a new greatness yet to come.

To Oporto: Part 4

The Knowledge

To Oporto: Part 4

The Knowledge

You'll most likely find Pedro, Ana and Bruno cooking up a storm at Pedro Limão at

If you want to know what happened to Lin Yee's tripe delve into her posts on thisismold

And if you want to taste Malka's famous cheescake rather than just read about it, head to The Good Egg in London

Bulhão Market is a good place for almost everything. It's falling apart, which is what makes it interesting,

but it's also set to be refurbished so will temporarily move, rumour has it to Porto's very own 'Guggenheim' car park.

Opposite have breakfast at Confeitaria do Bulhão and you'll start the day happy

Take home fruit, flower and vegetable seeds to sew in beautiful packets from Casa Hortícula on the corner

bought from the humble António Moreira da Silva who has worked there for 65 years.

Don't get excited by your find, everyone else got there first.

Padaria Ribeira will serve you top quality bread, salgados and all manner of sweet treats

Carnes Silmor is a haven for fresh meat

Salsicheria Leandro in Bulhão does a mean line in smoked sausages

Check out the neon on both

Thanks to Ana Carvalho, Bruno Senra and Pedro Limão for the inspiration, organisation, cooking and generosity

Estou tão feliz que voçes caíram na minha sopa!

And to the whole Travelogue Summer School crew for their good vibes,

stimulating conversation and the fine book we all made together

Photography © Rosanna Vitiello, Lin Yee Yuan, Casey Winkleman, Kate Brangan, Myrna D'Ambrosio

To Dungeness Part 1

To Dungeness

An anthology of abandoned narratives

To Dungeness Part 1

To Dungeness

An anthology of abandoned narratives

This stretch of English coast is not everyone's idea of paradise, but it does have its otherworldly charms. Nuclear power; pygmy footman moths; sound mirrors; artist's gardens. It's not often you mention this motley crew of landmarks in the same sentence, and that's why we went.

We got lucky, winding our way to Dungeness on a bright November day, with no more of an agenda than to find the concrete listening ears and make a delivery to the artist Paddy Hamilton. We found more of course. This corner of the Romney Marsh is a scavenger's dream; a place at the end of the road where loose ends gather. Wandering the shingle we discovered a phrase to describe this treasure-trove atmosphere: at once thrilling and lonely, Dungeness is a place of abandoned narratives.

The flat-lining landscape leaves everything on display, and yet everything to the imagination. The flotsam on-shore invites you to rummage and uncover threads of histories untangled, fishing crates of stories hauled in and strewn along the shore. Despite all the debris this desert feels alive. Migrant birds on global journeys call in, and the place is home to wild and weird species of plants and insects (the pygmy footman being one). Life on a shingle beach means the ground shifts constantly beneath you. Dungeness dwellers adapt to suit the new order and evidence of ingenuity is everywhere.

A BT truck is repurposed as a lobster pot storage unit

Queen Victoria’s train carriage is converted into a net-curtained family home

And so why couldn't a shingle fishing spit can become an artists' and architects' escape?

A lab for experimental listening devices?

And a controversial home for two nuclear power stations (A+B)?

To Dungeness Part 2

Pioneers

To Dungeness Part 2

Pioneers

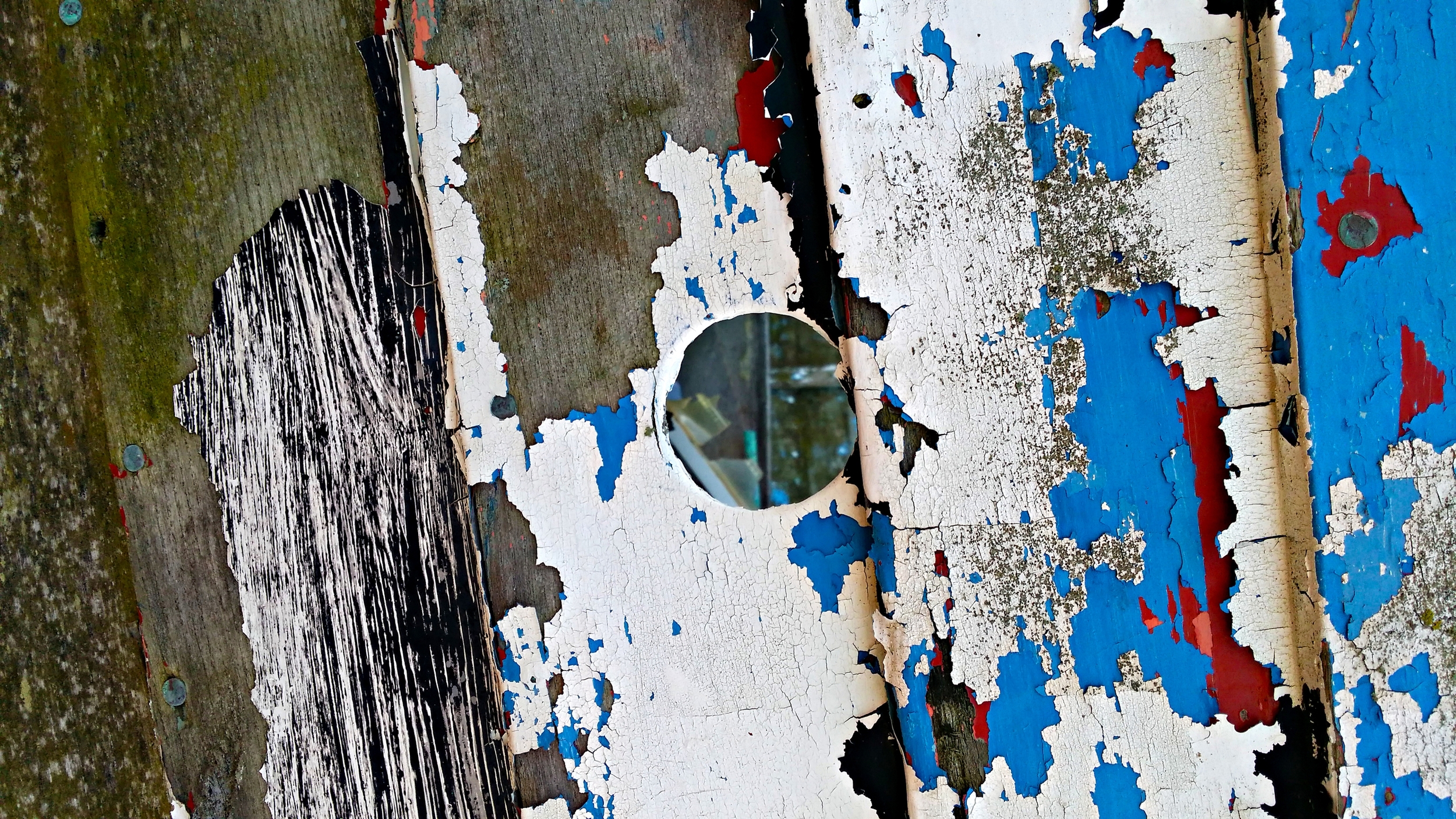

With constant change comes an attitude of abandon. Arm out-stretched ‘who gives a fuck?’freedom. Improvisation has always ruled in Dungeness, and the remnants of centuries of experiments mark the landscape. Marconi's tumbledown wireless shed housed research into radio-wave transmission in the 1890's. Thirty years later, the acoustic mirrors up the coast at Greatstone were prototyped as an early warning system to detect enemy aircraft. Since Derek Jarman's cottage has drawn a new focus, Dungeness has become an architectural laboratory with strict planning regulations to build on existing plots. One of the sparsest conversions is called Experimental Station, after its former use as a testing station for marine apparatus. "It reminds me of Marfa" said Jorge, and true that the flat expanses feel more like an artist's retreat in Texas than a Kent fishing community. But out here and isolated, people take on many roles and identities, and the loose ends start to tie together again.

Nuclear power artists and photo-shy armed guards

Concrete meteorologists and escape architects

Pirate illustrators and fishing trawler politicians

There are infinite stories to gather at Dungeness. The place is in itself an anthology. We picked up one thread to follow, and the rest remain there to be found...

To Dungeness Part 3

HOOK, LINE AND SINKER

The Politics of Fishing

To Dungeness Part 3

HOOK, LINE AND SINKER

The Politics of Fishing

I love buoys, but it's not what you're thinking. I'm talking the rotund, fluorescent type. Fishing is my thing and all the trappings of industry that come with it: nets, floats, anchors, crab pots, nylon rope and plastic buoys. It runs in the family. My great grandfather and his brother were fishermen, and owned a boat together. After a dramatic falling out, the stubborn (let's face it, stupid) siblings could come to no agreement, divided everything including the boat and sawed the vessel plain in half. So let's just say the politics of fishing is in my blood.

The beach at Dungeness is pockmarked with the debris of centuries of fishing politics. By the time we hit the shoreline, most of the fishermen are out at sea or in at home, and we give ourselves licence to rummage through these remnants. Between the Turner skies and rose-coloured seas, rivers of shingle nestle a good haul of fishing paraphernalia. Our catch, in pictures, as follows:

We trip over a rope winch pulled taught against the shingle, and Neco, walking beside me, drags up a memory:

"You know, this is how they took Constantinople?'

'With rusty engine winches?

'No, no. They said it could never be taken by sea, but the Ottoman's surprised them.

They dragged their boats over land and attacked from the behind, in sea to the North.'

The Byzantines fell for it. Boats and politics at war again.

Among tarred wooden huts exploding ancient nets, we gravitate towards the snack-shack on the promise of fish flatbreads. Poking a head through his open door, we get talking to the fishmonger next door about a bass. Dressed in wellies and woolly jumper, he tells us that 78% of the quota in the English Channel goes to French boats. The remaining 22% is shared between the Dutch, the Belgians and the English, which means about 10% of the Channel's catch comes to the UK. When the quotas were set, the French set their sights, estimated high and the EU went for it, hook, line and sinker. "We should have done the same" he laments, but his bass is still the freshest I've tasted.

"There were 29 boats here in the eighties. There are only four of us now."

The quotas are clues to the boat skeletons left here, shored up like a working graveyard. They say there were four fishing families in Dungeness who trace their trade back generations: the Tarts, the Oilers, the Thomases and the Richardsons. “My son went out on the boat at midnight last night,” explains our fishmonger, me in shock at the 12am commute, “it was his anniversary, so he had to celebrate before.” Their family use static net fishing on the Annalouison, but it's a tough way to make a living on in-shore fishing boats. “Fish blood everywhere, crab brains all over you!" laughs the artist, Paddy Hamilton, on life on a fishing boat. "It's carnage. And you’ve got to stay out the way of the drunk Russian tanker pilots powering on automatic down the Channel.”

Families hold fast, but practices evolve. Paddy reminisced about his boat-trips out with the fisherman. “They set their GPS to a point on the buoy and off they go. The best thing is when you close in on a buoy, the boat GPS sets its position to stay 3 metres away and just keeps moving,” and he dances back and forth in a fishing boat shuffle to impersonate the shifting hull.

"You can do that," says fishmonger, suggesting there's more to it. “You can follow all the boats on AIS, and call up the others to give you a wider berth.” AIS turns out to be a ship-spotter's digital wet dream: marine traffic websites tracking the movements of any shipping vessel in the world. Right now, the Riike Theresa tanker is headed to Las Palmas, the Stefan Sebum cargo vessel to Casablanca, and the Doreen T to Dungeness, all passing through the coastal waters off Kent, thick with vessels. It occurs to me that we call this 'The English Channel', which must have the French in bits: The English Channel!? A bit rich Britain laying claim to the whole stretch of water? The French call it La Manche, 'the sleeve', and if we can't agree on a name, what hope is there for the fishing rights?

Politics aside, there will always be the anglers, lining up like human markers along the shore. Angling is a waiting game. Slow and solitary, anglers pass the time staring out to the chameleonic sea and channel-flicking as tankers cruise a continuous course past. But the wait comes good: the weekly catches yield plentiful dogfish, dab, codling and pouting, and too many dreaded whiting, aided by 'The Boil'. A side-effect of the power stations' outflow pipes, the boil is a patch of waste hot water pumped into the sea and enriching life on the sea bed: a nuclear jacuzzi.

Dungeness offers no neat and happy ending. It just isn't that kind of place. This seaside desert is full of contradictions: a fishing-rope tug of war between wild sea and shingle; anglers and anti-nuclear activists; fishing boats and politicians. But you get the sense that if any of these fell here, Dungeness would shape-shift its identity, pick up another narrative thread and run with it.

Credits

The Knowledge

Credits

The Knowledge

Fish

Buy fish right off the boat from The Fish Hut or eat it there and then at The Snack shack

You can sign up to their mailing list or follow them on Facebook to find out what they're catching and cooking that day

In London, you can buy straight from the boats through Soleshare

Art

See the work of Paddy Hamilton or read an interview with Paddy at Weather Dependent

Stop by his open studios near the Lighthouse (and ask him about his Brazilian beach pencils)

There is a beautiful book on Derek Jarman's garden by his friend, photographer and film-maker Howard Sooley

Architecture

Stay in Dungeness at the Shingle House, designed by NORD, through Living Architecture

We've heard (from a lady at the pub) that a plot here will set you back £690,000

Simon Conder Associates have designed a number of the houses there

Nature

Follow Owen Leyshon, the Warden of the Romney Marsh Countryside Partnership on twitter @LeyshonOwen for as it happens updates on sitings of birds, insects, wildlife and to join events

He's knowledgeable and very friendly, so if you need more information call him on 01797 367934

Listening ears

Owen runs an open day at the sound mirrors every year, normally in mid-July, which allows you to go right up close

This is one of only two sites in the world where you can see all three designs of the ears

If you can't wait, park up on Hull Road in Lydd-on-Sea a mile or so North of Dungeness, and head inland across the shingle until you find a pathway

It's a strange mix of suburban wilderness and pre-war science

More details on Greatstone

You can't touch them, but you can get 'close enough to throw a cricket ball'

–

Thanks to all the No Fixed Abode Crew who made this first trip out-and-out great: Aycin, Neco, Allison, Ellie, Kirsten, Mert,Yeliz, Monica, Mike, Jorge, Daniel, Tess and the lovely Lisa for the concept of abandoned narratives. And to Kathy and Luciano for the copycat follow-up.

Photography © Rosanna Vitiello, Luciano Vitiello, Lisa Cumming, Kirsten Abildgaard